We’ve got too many hedgehogs. Not in our gardens, where they are disappearing at an alarming rate. There are too many hedgehogs in our workplaces.

Before I go any further, I love hedgehogs. One of my dearest friends, Hugh Warwick is a hedgehog about hedgehogs – an ecologist, author, activist, and presenter who uses his deep understanding of these well loved creatures to help us care more for the rich ecosystems around us.

When I say he is hedgehog-like I’m referring to “A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing” as the Ancient Greek poet Archilochus wrote.

In the well-trodden binary debate, given new life by the famous Isaiah Berlin’s essay , and now reinforced by the many articles posted on Linkedin and other places, there is a simplistic view of people either being Hedgehogs or Foxes.

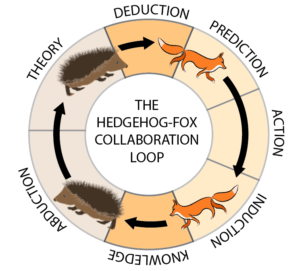

There are even some more helpful framings, such as this one looking at how foxes and hedgehogs can support each other in product development.

There are even some more helpful framings, such as this one looking at how foxes and hedgehogs can support each other in product development.

However, this reductive and binary view (spun out by Berlin more as a party game, rather than a serious categorisation) has become solidified into something less fun. Whether we like it or not (and I don’t) the modern economy has not only adopted this division, but decided that it’s also a good/bad dichotomy- where hedgehogs are good and foxes are bad.

The vast majority of jobs are increasingly specialised and mechanised – where, even in white-collar roles, we are production lines. We are selected, and trained (in school and in the work place) to be hedgehogs. Behavioural specificity is not only encouraged, it’s actively selected/recruited for. For example, in publishing, editorial folk are valued for detail, focus and compliance.

In the search for efficiency, value for money, and growth – key principles for most organisational leaders – on the basis that it’s far easier to organise a set of specialists, and outcomes are far more predictable.

Except, that’s not true. Like monocultures of all kinds, #DiversityWins for productivity, resilience and responsiveness. Organagrams force people into silos, and too often management processes keep them there. Although this system can function, it rarely flourishes.

Not only because ‘hedgehog’ specialists need more space, but because this system keeps out foxes. And without foxes: ranging across domains, omnivorous and curious; the cross fertilization needed for healthy growth just can’t happen. This is backed up by scientific observation of ecosystems.

A trophic cascade is what happens when an ecosystem is out of balance, often caused by the removal of a predator. An example of this is the removal of wolves, and the damage that deer can cause without an apex predator (more examples here)

In our workplaces, we’ve pushed out the foxes, into the wild. As Mark Barthelemy was saying earlier this week, “Generalists, who cross over the boundaries of many disciplines, are difficult to put into a box”. Mark points out that those who don’t ‘fit’ find themselves labelled ‘consultants’ – bought in to do the weird thing of thinking across departments, or bringing in learning from other sectors, or even reshaping boundaries.

Instead, we have the awkward sight of hedgehog leaders, promoted into generalist roles, trying to behave like foxes. You know what I mean: sales experts trying to lead product teams, engineers trying to manage and inspire designers, public relations specialists guiding the work of compliance officers. In other words, you have hedgehogs in fox clothing – Hedgefoxes, if you like.

More rarely, you might find a fox in a role where they are forced to focus on one thing. Foxhogs, perhaps. Just as in the other situation, the skin doesn’t fit and inevitably, if a fox’s true nature isn’t given space and valued, they’ll be quicker than a hedgehog to move on.

If it’s not already obvious – in this system, I’m a fox. Although I have acquired deep expertise, I don’t see myself as an expert – and as soon as I have understood the landscape of something, I am on to the next thing, making connections, backtracking to earlier discoveries, cross-fertilising ideas as I go.

So, here I am, freelance again, a fox for hire. If I could, for so many reasons, I’d rather be part of a team, but until we rewild the workplace, I am happier and more productive roaming free.