New EU regulations look set to bring some light into the often shady ‘Oil Rush’ in EdTech, drilling for data from our schools. Individuals will have new and powerful rights to their personal data, and organisation will have to show what use that information has been put to. In this post, I’ll look at what is actually going on with data now; what does the EU regulation mean; and what might change.

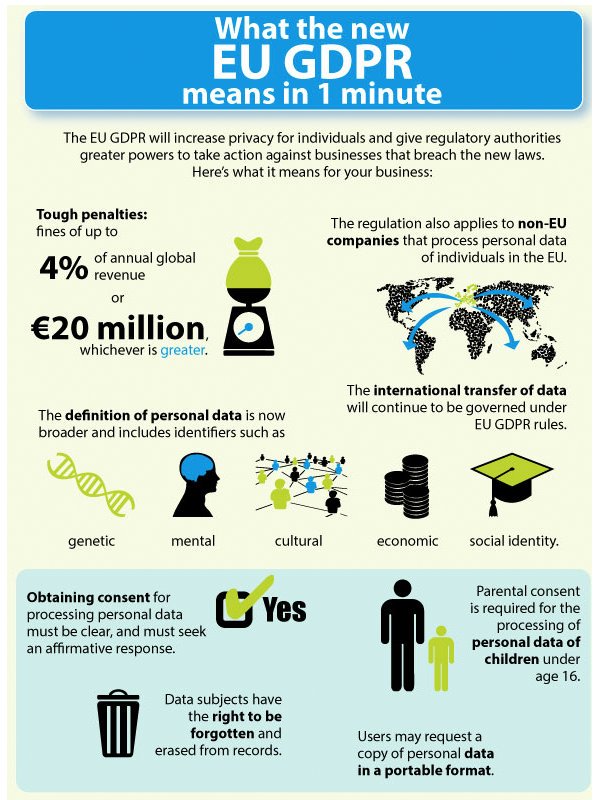

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will come into force on 25th May 2018, and (put simply) strengthens the rights of citizens over the data that their lives create. This useful Guardian article summarises the broader implications of the GDPR – and, NO, Brexit will not except UK citizens and organisations!

The new rights (in summary) are:

- Article 12: The right to have questions about use of personal data answered, and to seek redress if these questions are not answered in a clear, concise, timely manner.

- Articles 13 & 14: The right to know how personal data is being used at the time of collection, as well as the length of time for which it will be stored and contact information for the collecting party.

- Article 15: The right to access the personal data that is being processed.

- Article 16: The right to have incorrect personal data rectified.

- Article 17: The right to have personal data erased when they are no longer necessary for the purposes for which they were collected and there is no legal ground for their maintenance.

- Article 18: The right to restrict data processing where the data is inaccurate, its collection unlawful, or its processing no longer required.

- Article 19: The data collecting party must inform all additional data processors with whom it shares personal data to cease processing data that has been rectified or erased.

- Article 20: The right to receive their personal data in a structured, commonly-used, machine-readable format which they can freely share with other data processors.

- Article 21: The right to object to personal data being used to profile or market to them.

- Article 22: The right to not be subject to legal outcomes that rely solely on automated data processing.

For more detailed analysis – see here.

Like all the data protection regulations this new one replaces, GDPR will impact many aspects of school life. From fingerprints used to buy school lunches, to records of search terms used; school systems (MIS, assessment, attendance, LMS/VLEs) have been/are creating huge deposits of rich information about what goes on in classrooms and staffrooms.

The companies that run these systems are monetizing their access to this information – and, currently, have no need to check with the schools/children/parents – and neither do the third party organisations using that data. Though consent will not be a requirement of GDPR – there are implications that those offering edtech solutions need to consider. (Thanks to Tony Sheppard for his advice on getting my facts right here!)

If Data is the new ‘Oil’ – then the GDPR is an attempt to bring regulation on the wild oil rush that has been going on across many sectors, before those industries take too much control over the geology of our privacy.

In the 1900s there were only really four uses of crude oil. By the 1960s, as the image from 1957 below shows, that had grown to a complex tree. Now there is so much in our world that is a byproduct of fossil fuels, we seem unable / unwilling to undo our dependence, even though (most of us) know that it must happen.

So as we look ahead to see how our data might be used, we must protect children, because they are in our care (natch) – but also the learning spaces and professionals that are responsible for education. It is teachers, parents and children that should be at the core of how learning is created – not the algorithms and interests of data-mining vested interests.

Data driven learning has already created troubling developments, notably use of machine learning. As Audrey Watters, the self-styled Cassandra of Edtech, points out, there is also a worrying trend of appropriating progressive terms to deliver traditional models – where data is used to create personalised instruction – rather than personalised learning.

Though Early Years settings, Schools, FE and HE institutions should be/are preparing for this shift in regulation – they cannot predict how parents, children and students will make use of these new rights.

I would expect a series of landmark cases quite early on as professionals, parents and guardians apply for full disclosure on data collected about their children. I’ll certainly be doing that!

The revelations of where the data has gone, and the uses to which it has been put will uncover a complex picture which should start to explode and reshape the way that commercial interests use data extracted from learning spaces.

The sheer amount of ‘paperwork’ (ironic how that term applies even in this most digital of discussions) created by this new regulation will force new behaviours in businesses – but also in schools, and in the classroom.

If a teacher starts to collect information about how kids are learning, or looks at new models of assessment – they will have to map out the possible uses it might be put to – and the school will have to mark out provisions and mechanisms for parents to give consent. Will an unintended consequence of GDPR in schools be that teachers stop collecting data?

What will happen when children become adults, still in education, and seek to track back their data through to early years – and want to interact with the datasets and how that shaped the options and decision that impacted their educational opportunities?

Given the huge interest in developing AI for education, the ethical considerations raised by GDPR alone, threaten the pace of development and investment for these exciting – but troubling – technologies. What if an AI teaching support system develops a bias towards a set of interventions for a set of children? Could the algorithms that underpin that technology be construed as racist or sexist?

I’d be depressed if these questions and challenges to the use of technology formed a barrier to the evolution of how we educate our children. Instead, I hope that it will refocus the debate on the WHY rather than on the HOW. We know technology, and the data it creates, can help education improve, but, as citizens, we should do this in the open.

Instead of worrying about how GDPR will strangle innovation or development, I’d like to engage in discussions about how we create a more Open education system – where the data forms part of the learning interactions with students. This would mean a huge shift in our educational culture – and the systems that run our schools.

We need open systems for managing digital learning – especially assessment/credentialling. The Blockchain -through open Blockcerts – might offer a way to manage this new ecosytem – but it is only the start. As Doug Belshaw says, we also need to think about the ‘Weird and Wonderful’ aspects of education, that which data driven algorithms will struggle to interpret more effectively than human brains – and how we capture these in digital and meaningful ways.

If you are looking for specific, practical guidance, more detailed advice for schools is available – and is likely to become more readily available as we get closer to May 2018.

Until then, the debate is open – and the solutions should be too.

Pingback: The Top 10: Student Privacy News (July – August 2017) – Ferpa|Sherpa

Pingback: Read Write Respond #020 – Read Write Collect